Peter Jackson’s brave use of High Frame Rate (HFR) in “The Hobbit” has sparked intense debate over the past two months. The most prevalent questions have been:

Peter Jackson’s brave use of High Frame Rate (HFR) in “The Hobbit” has sparked intense debate over the past two months. The most prevalent questions have been:

“Does HFR look ‘better’ than traditional 24 fps, or does it just look ‘different’?”

“Will audiences eventually get used to HFR and then prefer it over traditional 24 fps, as with many other advances in motion imagery?”

Clearly HFR looks different. Anyone who saw “The Hobbit” in HFR can agree with that. And I think it’s fair to say that Jackson and his team succeeded in their goal to produce a more lifelike visual experience. But many viewers and critics found this new hyper-real experience off-putting, reducing the so-called “suspension of disbelief” that is considered essential to storytelling. Critics widely panned Jackson’s use of HFR, comparing the look of HFR to television and video games, deriding it as “non-cinematic,” “plasticine,” and “fake.”

If HFR didn’t work well for a cinematic adventure film like “The Hobbit,” there must be a scientific explanation. Or, as it turns out, maybe there isn’t. Yet…

At today’s Hollywood Post Alliance (HPA) Tech Retreat, Charles Poynton presented a fairly comprehensive overview of the challenges with motion imagery. His conclusion is that we don’t know enough about how motion is perceived by humans to explain with scientific certainty why HFR looks different. Poynton provided a thoughtful and detailed overview of how image capture and display technologies interact with the human perceptual system. Without going into detail about pulse width modulation or bit splitting (!) here are some of Poynton’s main points from today’s session:

- We are still trying to fully understand how motion is decoded in the brain. Some scientists believe the brain processes chunks of input (20 to 50 milliseconds each) while others believe perception is more like a continuous stream.

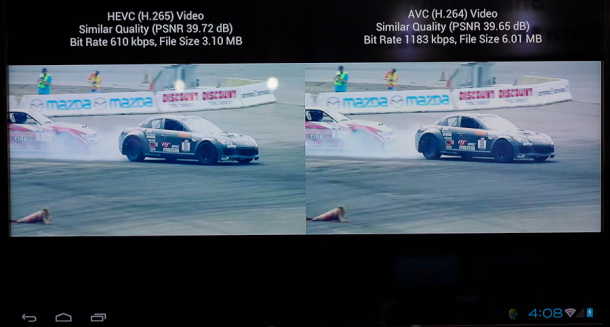

- Despite advances in our learning about human perception, along with advances in algorithms that use these learnings to automatically assess visual quality, the only way to conclusively assess visual quality remains subjective testing by humans.

- The way that humans track motion, by moving their eyes several times per second, presents a challenge for motion imaging systems.

- Different display technologies (LCD, Plasma, DLP, CRT) emit light in different ways over time, creating an additional factor that must be carefully optimized.

- Along with wide gamma and other advances in motion image technology, HFR needs further study and refinement before it can be successfully adopted.

As a fitting postscript to Poynton’s presentation, Mark Schubin suggested that not only do we not yet know why HFR looks so different from traditional 24 fps, we also don’t know where this will all land. Many other advances in cinema technology were initially rejected by viewers, but eventually became standard fare.

In my opinion, HFR will eventually be incorporated as an additional, valuable tool for storytellers. Higher frame rates are not inherently superior to 24 fps for all content genres, but they may meaningfully enhance the audience experience when used for scenes that require fast motion or hyper-reality. It may turn out that some television genres like news, live entertainment and sports may be better suited to high frame rates, because the goal of these productions is to approximate live attendance of the event. Dramatic programs with high production values, such as The Hobbit, may ultimately benefit from the suspension of disbelief induced by the cinematic look of 24 fps, incorporating HFR more sparingly as a visual effect.

So maybe HFR is not the problem – maybe we are. Notwithstanding the creativity and skill of Peter Jackson and his team, perhaps we don’t know how to do HFR well yet. Maybe we don’t yet know when to use HFR and when not to. But at least Peter Jackson has forced the discussion by boldly pushing into this new frontier, for which we can all be grateful.