TV’s will be available this year, but adoption will be slow.

Not surprisingly, Ultra High Definition Television (UHDTV for short) was the big buzz at CES last week. All of the major TV manufacturers were demonstrating UHDTV sets running at 4K resolution, with Sharp showing an updated prototype 85” TV running at 8K resolution. But even as the TV sets themselves are approaching availability, the picture is becoming increasingly clear (pun intended) that uptake will be slow.

- Although UHDTV sets will be available as soon as March of this year, initial pricing will be prohibitively high (>$10,000). According to CEA analysts, UHDTV units will account for only 5% of TV’s sold in 2016.

- No 4K or 8K content is available currently to view on UHDTV sets and likely won’t be available in quantity for years to come.

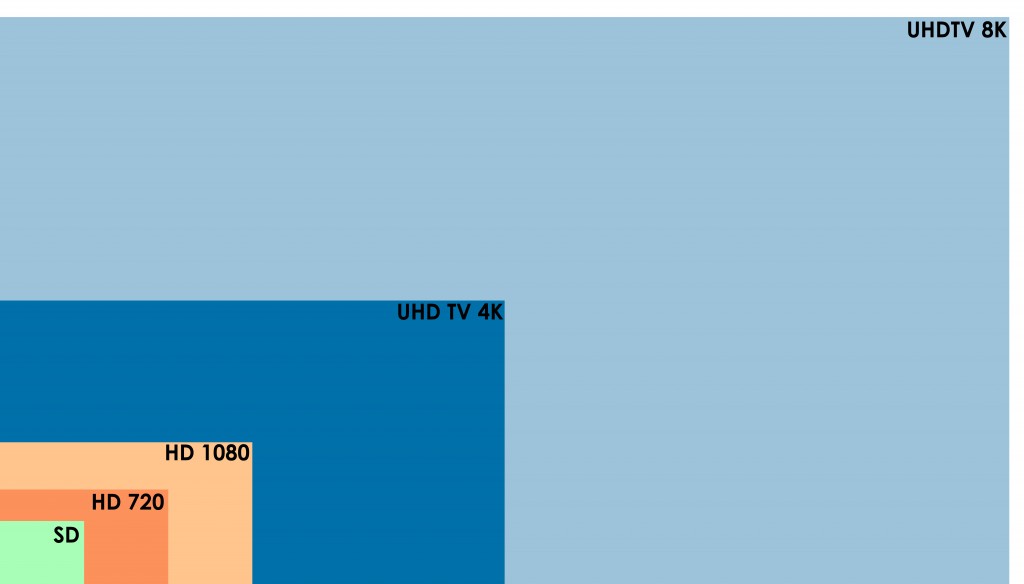

- There is currently no distribution method for UHDTV content. Data rates for UHDTV can be at least four to sixteen times higher than for 1080p HD.

- Broadcasters are generally unconvinced that a viable business model will emerge for UHDTV.

- Most industry analysts and TV vendors now acknowledge that UHDTV has little (if any) value for displays smaller than 50 inches. For my thoughts on the relative value of higher spatial resolution, please read my earlier post on this topic.

In short, UHDTV is a really impressive technology that is desperately in search of a market opportunity. It’s hard to dispute that UHDTV represents a future we can all get excited about, but (like HD before it) the market for UHDTV will likely take several years to develop. Read on if you want more of the gory details. If you’re a UHDTV novice, feel free to check out the primer on UHDTV I posted last September.

(photo courtesy of pocket-lint.com)

UHDTV’s Will Be Available Soon

Virtually all of the major TV vendors demonstrated UHDTV sets at CES last week. Note that none of the sets is currently available, but some will begin shipping as soon as March 2013. Early units will include 94-inch displays from Sony and LG that will be priced at $20,000-$25,000. Smaller models will cost less – the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA) estimates that the average wholesale cost of 4K televisions will drop to $7,000 by late 2013, then to $2,800 in 2014. Even with this steep decline in price, only 1.4 million unit sales are projected for the U.S. in 2016, equivalent to roughly 5% of the market.

“It’s a very, very limited opportunity,” said Steve Koenig, director of industry analysis at the CEA. “The price points here are in the five digits (in U.S. dollars) and very few manufacturers, at least at this stage, have products ready.”

Content is (Lac)King

No UHDTV content is available to consumers currently. But the technology is available to create 4K content. Increasingly, feature films are shot with 4K cameras and are mastered at 4K for theatrical distribution. 4K consumer camcorders are already on the market. Classic films archived on 35mm film could be retransferred at 4K for distribution. And gaming engines could fairly easily render images in 4K or 8K. So the technology is available, but until a compelling market opportunity exists, content owners may not jump on board.

Upscaling and Other Sources

Early UHDTV sets from vendors like Samsung, Sony and Toshiba, will support upscaling of HD content to 4K. For example, Sony recently announced plans for a “Mastered in 4K” Blu-ray library that will offer content mastered in 4K that is downscaled to 1080p HD for Blu-ray release.

“When upscaled via the Sony 4K Ultra HD TVs, these discs serve as an ideal way for consumers to experience near-4K picture quality,” according to Sony.

While this may seem like a sketchy marketing ploy (because the discs are no different from today’s Blu-ray titles) I have to admit that standard def DVD’s look much better when upscaled to HD, so there is a possibility that Blu-ray discs will look even better when upscaled to UHDTV. Still, upscaling of 1080p content is at best a stopgap until UHDTV-native content becomes available.

One source of UHDTV-native content could be your computer. Graphics cards have long since surpassed the 1920×1080 resolution of HD. Home movies and photo montages will look great on a huge UHDTV. I can also imagine UHDTV’s becoming commercially viable as high-end displays for retail and corporate applications. But for television viewing, the lack of native UHDTV content will definitely be a barrier to adoption.

Bandwidth and Distribution

At 4K, UHDTV content has more than four times as many pixels as HD. At 8K, that multiplier jumps to >16x. Carrying that much data will require significant advances in compression technology as well as increases in network bandwidth. Ironically, at a time when sales of physical media are plummeting, these challenges may make physical media the most practical method for distributing UHDTV for the next few years. Recently, the Blu-Ray Disk Association has formed a task force to study the viability of extending the Blu-ray format to support 4k.

As for television, some broadcasters seem interested in exploring UHDTV. Recently, satellite operator Eutelsat Communications launched a demonstration 4K channel in Europe. And an experimental Ultra HD channel is also being planned in Korea. NHK in Japan hopes to begin experimental 8K broadcasts in 2020. But these technology experiments are primarily focused on exploring the technical viability of UHDTV broadcast.

Business Model

Market viability is perhaps the biggest question surrounding UHDTV broadcast. As with the 3D hype two years ago, some industry analysts expect sports programming to drive consumer interest in UHDTV.

The Hollywood Reporter recently stated that “BSkyB in the UK, Sky Deutschland in Germany, Japan’s Sky Perfect Jsat, and Brazil’s TV Globo have all started to explore the potential of 4K, which would include coverage of events such as sports…with an eye toward offering the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympics (both of which will be held in Brazil) in [UHDTV].”

But other broadcasters have gone on record as much more jaundiced about the market opportunity. During the Broadband Unlimited conference at CES last Monday, Sheau Ng, VP of research and development for NBC Universal says there’s no business model for UHD TV yet.

“Therein lies the rub,” Ng said. “It’s not the technology, it’s the business model. Where is the money? Unlike the previous revolution of HD, we have the device manufacturers selling the device when people are still scratching their head and saying ‘What do I do?’ That’s something we’re wrestling with every day. For us to say ‘We’re going to do this,’ we need somebody to say ‘here’s the business model, here’s the number of devices in the market, here’s how we’re going to make money.’”

And Bryan Burns, VP of strategic business planning and development at ESPN, hinted that some broadcasters will wait for 8k.

“By the time we get [to 4K] we will be on to 8K or whatever. I don’t want to make the capital investment [in 4K]. There might be a gradual evolution…but I don’t see us heading to 4K production or an ESPN 4K channel.”

In Summary…

With the proliferation of high resolution cameras and displays, the question surrounding UHDTV is no longer “how,” so much as “why” and “when.” From my perspective, until there is critical mass of UHDTV sets installed in homes, content owners won’t spend the extra dollars to make UHDTV content available. Until the content is available, broadcasters won’t create UHDTV channels. And until a lot of compelling content is both available and affordable, consumers won’t pay extra for UHDTV sets or service.

If this circular “chicken and egg” dynamic sounds to you a lot like the uphill battle faced by HD technology fifteen years ago, or 3D TV two years ago, I think you’ve gotten my point: UHDTV is definitely coming, but not quickly.